Intro

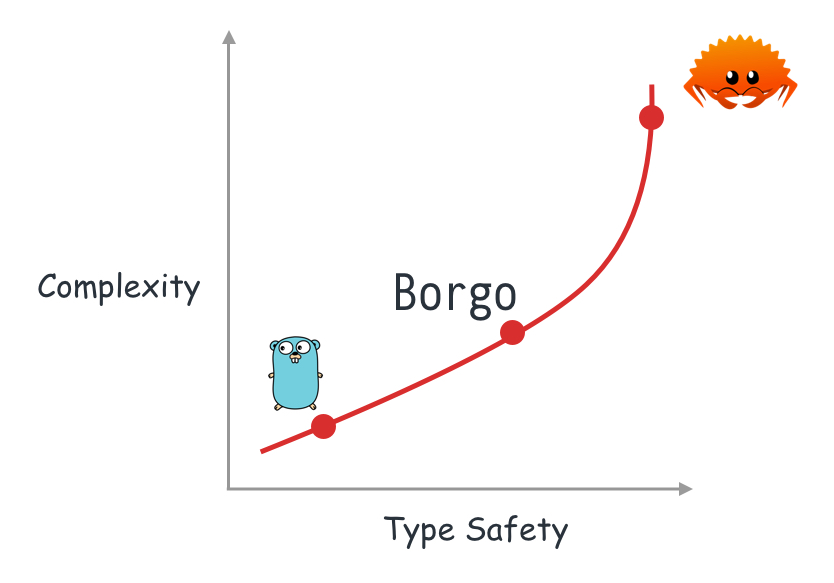

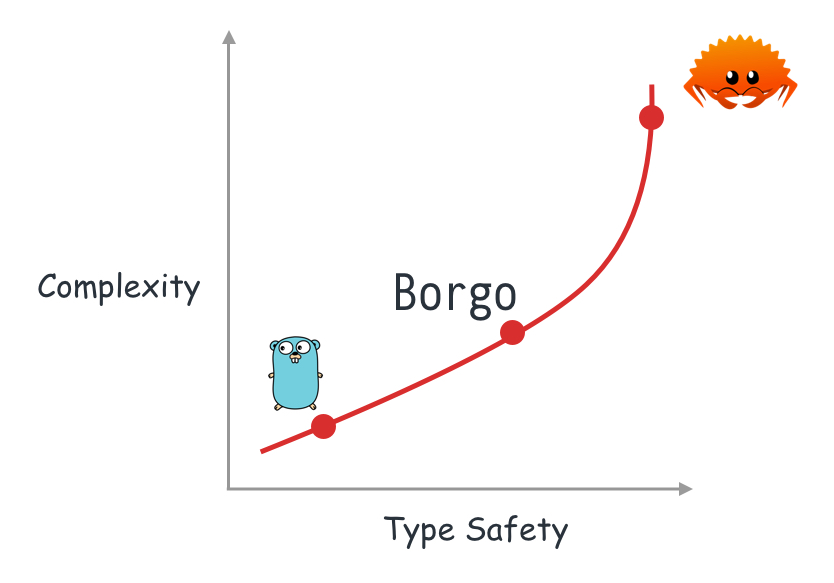

Borgo is a new programming language that compiles to Go.

For a high-level overview of the features and instructions on running the

compiler locally, check the

README.

This playground runs the compiler as a wasm binary and then sends the transpiled

go output to the official Go playground for execution.

use fmt

enum NetworkState<T> {

Loading,

Failed(int),

Success(T),

}

struct Response {

title: string,

duration: int,

}

fn main() {

let res = Response {

title: "Hello world",

duration: 0,

}

let state = NetworkState.Success(res)

let msg = match state {

NetworkState.Loading => "still loading",

NetworkState.Failed(code) => fmt.Sprintf("Got error code: %d", code),

NetworkState.Success(res) => res.title,

}

fmt.Println(msg)

}

Primitive Types

Primitive types are the same as in Go.

Collections like slices and maps can be used without specifying the type of the

values.

For example, a slice of int elements would be declared as []int{1,2,3} in Go,

whereas Borgo relies on type inference to determine the type, so you can just

write [1, 2, 3].

Functions like append() and len() are available as methods.

Maps are initialized with the Map.new() function, which under the hood

compiles to a map[K]V{} expression, with the K and V types helpfully

filled in for you.

Borgo also has tuples! They work exactly like in Rust.

Multiline strings are defined by prefixing each line with \\ like in Zig. This

has the benefit that no character needs escaping and allows more control over

whitespace.

use fmt

fn main() {

let n = 1

let s = "hello"

let b = false

fmt.Println("primitives: ", n, s, b)

let mut xs = [1,2,3]

fmt.Println("slice:", xs)

xs = xs.Append(10)

fmt.Println("len after append:", xs.Len())

let mut m = Map.new()

m.Insert(1, "alice")

m.Insert(2, "bob")

fmt.Println("map:", m)

let pair = ("hey", true)

fmt.Println("second element in tuple:", pair.1)

let multi = \\a multi line

\\ string with unescaped "quotes"

\\ that ends here

fmt.Println("multiline string:", multi)

}

Control flow

Like in Go, the only values that can be iterated over are slices, maps, channels

and strings.

However, loops always iterate over a single value, which is the element in the

slice (contrary to Go, where using a single iteration variable gives you the

index of the element).

To iterate over (index, element) pairs call the .enumerate() method on

slices. This has no runtime cost, it just aids the compiler in generating the

correct code.

When iterating over maps, you should always destructure values with

(key, value) pairs instead of a single value.

Like in Rust, infinite loops use the loop {} construct whereas loops with

conditions use while {}.

Expressions like if, match and blocks return a value, so you can assign

their result to a variable.

use fmt

use math.rand

fn main() {

let xs = ["a", "b", "c"]

fmt.Println("For loop over slices")

for letter in xs {

fmt.Println(letter)

}

fmt.Println("Indexed for loop")

for (index, letter) in xs.Enumerate() {

fmt.Println(index, letter)

}

let m = Map.new()

m.Insert(1, "alice")

m.Insert(2, "bob")

fmt.Println("For loop over maps")

for (key, value) in m {

fmt.Println(key, value)

}

fmt.Println("Loop with no condition")

loop {

let n = rand.Float64()

fmt.Println("looping...", n)

if n > 0.75 {

break

}

}

fmt.Println("While loop")

let mut count = 0

while (count < 5) {

fmt.Println(count)

count = count + 1

}

fmt.Println("using if statements as expressions")

fmt.Println(if 5 > 3 { "ok" } else { "nope" })

let block_result = {

let a = 1

let b = 2

a + b

}

fmt.Println("block result:", block_result)

}

Algebraic data types and pattern matching

You can define algebraic data types with the enum keyword (pretty much like

Rust).

Pattern matches must be exhaustive, meaning the compiler will return an error

when a case is missing (try removing any case statement from the example and see

what happens!).

For now, variants can only be defined as tuples and not as structs.

use fmt

use strings

enum IpAddr {

V4(uint8, uint8, uint8, uint8),

V6(string),

}

fn isPrivate(ip: IpAddr) -> bool {

match ip {

IpAddr.V4(a, b, _, _) => {

if a == 10 {

return true

}

if a == 172 && b >= 16 && b <= 31 {

return true

}

if a == 192 && b == 168 {

return true

}

false

}

IpAddr.V6(s) => strings.HasPrefix(s, "fc00::")

}

}

enum Coin {

Penny,

Nickel,

Dime,

Quarter,

}

fn valueInCents(coin: Coin) -> int {

match coin {

Coin.Penny => 1,

Coin.Nickel => 5,

Coin.Dime => 10,

Coin.Quarter => 25,

}

}

fn main() {

let home = IpAddr.V4(127, 0, 0, 1)

let loopback = IpAddr.V6("::1")

fmt.Println("home ip is private: ", home, isPrivate(home))

fmt.Println("loopback: ", loopback)

let cents = valueInCents(Coin.Nickel)

fmt.Println("cents:", cents)

}

Structs

Defining and instantiating structs is similar to Rust.

Contrary to Go, all struct fields must be initialized. See the section on nil

and zero values for more information.

use fmt

struct Person {

name: string,

hobbies: [Hobby],

}

enum Hobby {

SkyDiving,

StaringAtWall,

Other(string),

}

fn main() {

let mut p = Person {

name: "bob",

hobbies: [Hobby.StaringAtWall, Hobby.Other("sleep")],

}

fmt.Println("person:", p)

p.hobbies = p.hobbies.Append(Hobby.SkyDiving)

fmt.Println("with more hobbies:", p)

}

Result and Option

Sometimes it's helpful to deal with values that may or may not be there. This is

the idea behind the Option<T> type.

For example, to get an element out of a slice or a map, you can use the

.get(index) method that will force you to handle the case where the element

isn't there.

Other times you may want to return a value or an error. In those cases use

Result<T, E> to let the caller know that a function may return an error.

When you're sure that a value is definitely there, you can call .unwrap().

Like in Rust, this is an unsafe operation and will panic.

A lot of methods are missing from both Result and Option, contributions to

the stdlib are welcome!

use fmt

struct Person {

name: string,

age: int

}

fn validate(name: string, age: int) -> Result<Person, string> {

if (age < 18) {

return Err("too young")

}

if (age > 98) {

return Err("too old")

}

Ok(Person { name, age })

}

fn main() {

let xs = ["a", "b", "c"]

let element = xs.Get(2) // Option<string>

match element {

Some(s) => fmt.Println("ok, the element was found:", s),

None => fmt.Println("element not found"),

}

let result = validate("alice", 33) // Result<Person, string>

match result {

Ok(p) => fmt.Println("got a person:", p),

Err(e) => fmt.Println("couldn't validate:", e),

}

}

Interoperability with Go

One ambitious goal of this project is to be fully compatible with the existing

Go ecosystem.

You've already seen how the fmt package was used in previous examples, but how

do we deal with functions that return multiple values?

This is where our trusty Option and Result types come in! The compiler will

handle the conversion automatically for you :)

A good mental model is to think of return types in Go functions as:

when return type is (T, bool)

it becomes Option<T>

when return type is (T, error)

it becomes Result<T, E>

Let's take the os.LookupEnv function as an

example:

Go definition:

func LookupEnv(key string) (string, bool)

becomes:

fn LookupEnv(key: string) -> Option<string>

Or the os.Stat function from the same package:

Go definition:

func Stat(name string) (FileInfo, error)

becomes:

fn Stat(name: string) -> Result<FileInfo>

Result<T> is short-hand for Result<T, error> where error is the standard

Go interface.

With this simple convention, pretty much any Go package can be used in Borgo

code! All is needed is a package declaration, which is discussed in the next

section.

use fmt

use os

fn main() {

let key = os.LookupEnv("HOME")

match key {

// Option<T>

Some(s) => fmt.Println("home dir:", s),

None => fmt.Println("Not found in env"),

}

let info = os.Stat("file-does-not-exist")

match info {

// Result<T, E>

Ok(_) => fmt.Println("The file exists"),

Err(err) => fmt.Println("Got error reading file", err),

}

}

Package definitions

In order to use existing Go packages, Borgo needs to know what types and

functions they contain. This is done in declaration files, which serve a similar

purpose to what you might see in Typescript with d.ts files.

Only a small part of the Go stdlib is currently available for use in Borgo --

check the std/ folder for

more information.

The example on the right uses the regexp package from the Go standard library.

The relevant bindings are defined in std/regexp/regexp.brg (here's a snippet):

struct Regexp { }

fn Compile (expr: string) -> Result<*Regexp> { EXT }

fn CompilePOSIX (expr: string) -> Result<*Regexp> { EXT }

fn MustCompile (str: string) -> *Regexp { EXT }

fn MustCompilePOSIX (str: string) -> *Regexp { EXT }

fn Match (pattern: string, b: [byte]) -> Result<bool> { EXT }

// ... other stuff

Writing such declarations by hand is a pain! There's no reason why this process

couldn't be automated though. The compiler comes with an importer tool that

parses a Go package and generates corresponding bindings to be used in Borgo.

use fmt

use regexp

fn main() {

let validID = regexp.MustCompile("^[a-z]+[[0-9]+]$")

fmt.Println(validID.MatchString("adam[23]"))

fmt.Println(validID.MatchString("eve[7]"))

}

Pointers and References

Pointers and References work the same as in Go.

To dereference a pointer, use foo.* instead of *foo (like in Zig).

use fmt

struct Foo {

bar: int

}

struct Bar {

foo: *Foo

}

fn main() {

let mut f = Foo { bar: 0 }

let b = Bar { foo: &f }

f.bar = 99

fmt.Println(b.foo)

// pointer dereference

// In Go, this would be: *b.foo = ...

b.foo.* = Foo { bar: 23 }

fmt.Println(b.foo)

}

Methods

To define methods on types, you can use impl {} blocks.

In Go, the method receiver must be specified at each function declaration. In

Borgo, this is specified only once at the beginning of the impl block

(p: *Person). All functions within the block will have that receiver.

It's also possible to declare static methods: functions can be declared with

dots in their name, so you can define a Person.new function like in the

example.

use fmt

struct Person {

name: string,

hours_slept: int,

}

fn Person.new(name: string) -> Person {

Person {

name,

hours_slept: 0,

}

}

impl (p: *Person) {

fn sleep() {

p.hours_slept = p.hours_slept + 1

}

fn ready_for_work() -> bool {

p.hours_slept > 5

}

fn ready_to_party() -> bool {

p.hours_slept > 10

}

}

fn main() {

let mut p = Person.new("alice")

p.sleep()

p.sleep()

fmt.Println("is ready:", p.ready_for_work())

}

Interfaces

Interfaces in Borgo work the same as in Go, it's all duck typing.

If a type implements the methods declared by the interface, then the type is an

instance of that interface.

Embedded interfaces are also supported, just list out the other interfaces

implied by the one being defined (prefixed by impl). For example, the

ReadWriter interface from the io package can be defined as:

interface ReadWriter {

impl Reader

impl Writer

}

type sets are not supported.

use fmt

use math

interface geometry {

fn area() -> float64

fn perim() -> float64

}

struct rect {

width: float64,

height: float64,

}

impl (r: rect) {

fn area() -> float64 {

r.width * r.height

}

fn perim() -> float64 {

2 * r.width + 2 * r.height

}

}

struct circle {

radius: float64,

}

impl (c: circle) {

fn area() -> float64 {

math.Pi * c.radius * c.radius

}

fn perim() -> float64 {

2 * math.Pi * c.radius

}

}

fn measure(g: geometry) {

fmt.Println(g)

fmt.Println(g.area())

fmt.Println(g.perim())

}

fn main() {

let r = rect {

width: 3,

height: 4,

}

let c = circle { radius: 5 }

measure(r)

measure(c)

}

Error handling

In functions that return a Result, it's possible to propagate errors with the

? operator.

This is similar to what happens in Rust, refer to the section on

Propagating errors

in the Rust book .

Currently the ? operator only works with Result, but it will be extended to

also work with Option.

use fmt

use io

use os

fn copy_file(src: string, dst: string) -> Result<(), error> {

let stat = os.Stat(src)?

if !stat.Mode().IsRegular() {

return Err(fmt.Errorf("%s is not a regular file", src))

}

let source = os.Open(src)?

defer source.Close()

let destination = os.Create(dst)?

defer destination.Close()

// ignore number of bytes copied

let _ = io.Copy(destination, source)?

Ok(())

}

fn copy_all_files(folder: string) -> Result<int, error> {

let mut n = 0

for f in os.ReadDir(folder)? {

if !f.IsDir() {

let original = f.Name()

let new_name = fmt.Sprintf("%s-copy", original)

fmt.Println("copying", original, "to", new_name)

copy_file(original, new_name)?

n = n + 1

}

}

Ok(n)

}

fn main() {

match copy_all_files(".") {

Ok(n) => fmt.Println(n, "files copied"),

Err(err) => fmt.Println("Got error:", err),

}

}

Zero values and nil

In Borgo, you can't create nil values.

The concept of null references (or nil in this case) is being referred to as

"The billion dollar mistake" and modern languages are moving away from it with

types like Option<T>. Borgo tries to do the same.

You can still end up with null pointers if you're calling into existing Go code,

which is unfortunate. That should be solvable by writing better bindings, so

that functions that could return a null pointer, will instead return an

Option<*T>, forcing you to handle all cases.

In Go, it's common to see types not needing to be initialized, as their zero

value is ready to be used (ie. sync.Mutex or sync.WaitGroup). Borgo goes in

the opposite direction, requiring that all values are explicitely initialized.

You can use the built-in function zeroValue() whenever you need the zero

value of a type. While you won't need to provide a type annotation in all cases

(as the type can be inferred), it's probably clearer to annotate variables that

are initialized with zeroValue().

As mentioned in a previous section, this also applies to struct fields, which

always need to be initialized.

use sync

use bytes

use fmt

fn main() {

// in Go:

// var wg sync.WaitGroup

let wg: sync.WaitGroup = zeroValue()

// in Go:

// var b bytes.Buffer

let b: bytes.Buffer = zeroValue()

fmt.Println("variables are initialized:", wg, b)

}

Concurrency (goroutines)

Borgo aims to support all concurrency primitives available in Go.

Use the spawn keyword (instead of go) to start a goroutine. The parameter

needs to be a function call.

Channels and select {} statements are discussed next.

use sync

use fmt

struct Counter {

count: int,

mu: sync.Mutex,

}

fn Counter.new() -> Counter {

Counter { count: 0, mu: zeroValue() }

}

impl (c: *Counter) {

fn Inc() {

c.mu.Lock()

c.count = c.count + 1

c.mu.Unlock()

}

}

fn main() {

let desired = 1000

let counter = Counter.new()

let wg: sync.WaitGroup = zeroValue()

wg.Add(desired)

let mut i = 0

while (i < desired) {

// equivalent to: go func() { ... }()

spawn (|| {

counter.Inc()

wg.Done()

})()

i = i + 1

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Counter value:", counter.count)

}

Channels

Borgo doesn't provide any extra syntax to send/receive from channels.

You use Channel.new() to create a Sender<T> and Receiver<T>.These are

roughly equivalent to send-only and receive-only channels in Go and will compile

to raw channels in the final Go output.

With a Sender<T> you can call send(value: T) to send a value. With a

Receiver<T> you can call recv() -> T to receive a value.

This design is somewhat inspired by the sync::mspc::channel module in the Rust

standard library.

use fmt

fn main() {

let (sender, receiver) = Channel.new()

spawn (|| {

sender.Send(1)

})()

spawn (|| {

sender.Send(2)

})()

let msg = receiver.Recv()

let msg2 = receiver.Recv()

fmt.Println(msg + msg2)

}

Select statements

select {} works like in Go, however the syntax is slightly different.

Reading from a channel

Go: case x := <- ch

Borgo: let x = ch.Recv()

Sending to a channel

Go: case ch <- x

Borgo: ch.Send(x)

Default case

Go: default

Borgo: _

use fmt

use time

fn main() {

let (tx1, rx1) = Channel.new()

let (tx2, rx2) = Channel.new()

// dummy done channel

let (_, done) = Channel.new()

spawn (|| {

tx1.Send("a")

})()

spawn (|| {

loop {

select {

// in Go:

// case tx2 <- "b":

tx2.Send("b") => {

fmt.Println("sending b")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

let _ = done.Recv() => return

}

}

})()

select {

// in Go:

// case a := <- rx1:

let a = rx1.Recv() => {

fmt.Println("got", a)

},

let b = rx2.Recv() => {

fmt.Println("got", b)

},

}

}